Computer Vision

A Technical Survey

Foreword

This is a guest blog by Stephen Phillips, a Ph.D. student in computer vision at The University of Pennsylvania. He will give us a broad introduction of computer vision, in particular delineate the difference between "computer-vision for the web", which has the seat of much recent hype, and computer vision applied to the physical world, which necessitates much more geometric understanding. And finally, what is the deal with deep learning? Stephen will demystify this for us well.

Introduction

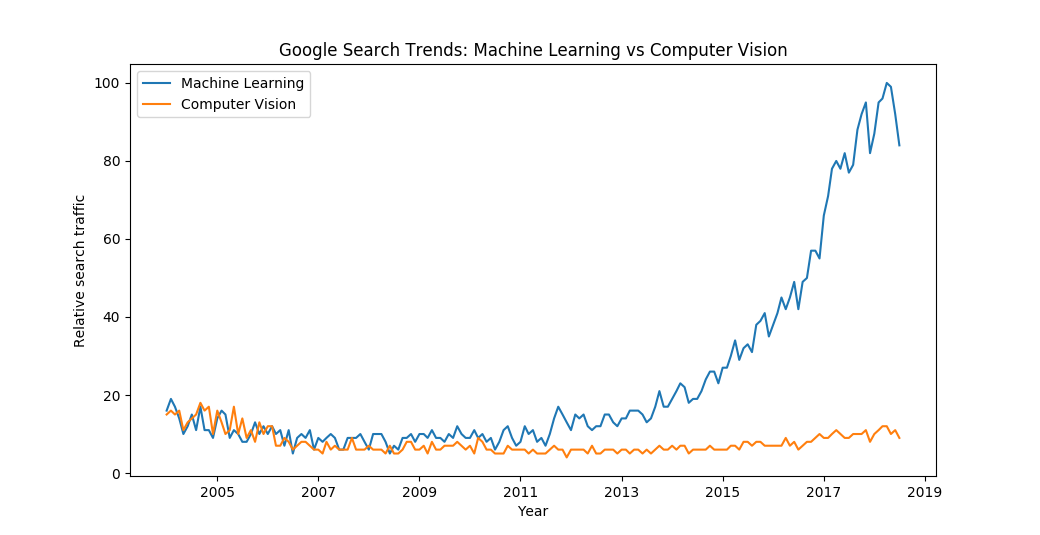

I’m sure you have heard of Machine Learning. However, if Google Search Trends are any indication, Computer Vision seems to be less known:

The fields are closely related. The meteoric rise of Machine Learning was in part caused by successes in Computer Vision a few years ago. So what is Computer Vision? Put simply it is the study of automated understanding of images. Recognizing objects in images, detecting the pose of humans, labelling every pixel as being part of a road or not, getting precise 3D reconstructions of a room from a video - these all fall under the umbrella of Computer Vision.

Why do we care? Well, as it turns out, Computer Vision is useful in many domains. You may not realize it but Computer Vision applications have been around since the 1990s. One early application was automatically recognizing zip codes on letters for the US Postal Service. Another early application was 3D motion capture, which admittedly only worked in limited environments, a common constraint imposed by the limitations of early Computer Vision technologies.

With recent developments in Computer Vision, the applications have become much more broadly applicable. Google image search now uses Computer Vision as opposed to tags to label images. You can also search for terms in Google Photos without needing to tag the images. Facebook also plays this game, using Computer Vision to automatically detect faces in images. Google Earth was an early example of 3D reconstruction at massive scale, using millions of images stitched together using 3D reconstruction algorithms to create the 3D mesh of the world. We are also seeing this at a smaller scale with Virtual and Augmented Reality (e.g. Pokemon Go) and its recent rise. And finally the looming monolith, the self-driving car, where cameras are a good complementary sensor for things like obstacle detection and sign reading. Given the wide range of applications and the huge investments behind them, it is important part of due diligence to understand the current state of Computer Vision - its strengths and limitations. So... onward!

Background - or why Computer Vision is Difficult

Before we get to the more interesting part, the solutions to Computer Vision problems, it helps to first understand why Computer Vision in general is a hard problem. Vision to us humans is so simple and intuitive it can be hard to imagine why it would be hard. At least that is what early Artificial Intelligence researchers at MIT thought, thinking they could solve object detection in a summer (to see the original proposal look here). Well, it took a bit longer than that - in fact, we are still working on it 50 years later.

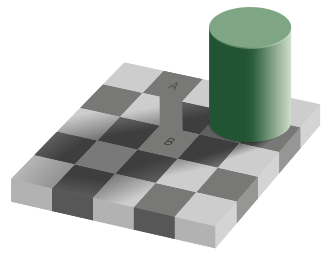

Why did it stump them? Let’s put our engineering hats on, and look at the task of object detection. To give you a simple example, we want to determine if there is a cat in a picture or not. The only way to do this we need to work on the computer’s representation of the picture - so how does a computer store this picture? Well, it stores a 2D array of color values (each one represented as three 8-bit numbers for the Red-Green-Blue values). Unfortunately a 2D array of pixels is an awful thing to work with. The color of a pixel doesn’t tell you much - consider the following optical illusion:

When we see tiles A and B, we know that they are different colors - A is dark grey, B is white. Our brains can infer this because we understand that tile B is under a shadow, and thus the true color, so to speak, is brighter than what it appears. However, to a computer processing this, there is no difference between these tiles. If you work directly with the colors, you cannot distinguish these tiles. This is a specific instance of the more general problem of color variance. Going back to the cat example, cats come in many different fur colors, so a simple color check doesn’t work. But it gets worse. Even the same cat in various lighting conditions can have drastically different color values in pixels - a cat in sunlight looks different than a cat in fluorescent light which again looks different than a cat in a dark room. But they are all still the same cat. Also note that the cat can take up different portions of the image - a picture of cat taken close or far away look pretty different with respect to the pixels.

However, it gets even worse. Cats, unfortunately for us, don’t stand in the same posture all the time. We can see cats in many different postures - standing on 4 legs, laying on their belly, laying on their back, jumping, purring, meowing, and infinitely more. We also can see the cat from many different angles - from above, below, the side, the front, the back, and any angle in between. A picture of a cat jumping from above has a completely different set of pixels than a picture of cat walking from the side. Yet we have to say ‘yes, there is a cat in that picture’ to both of them.

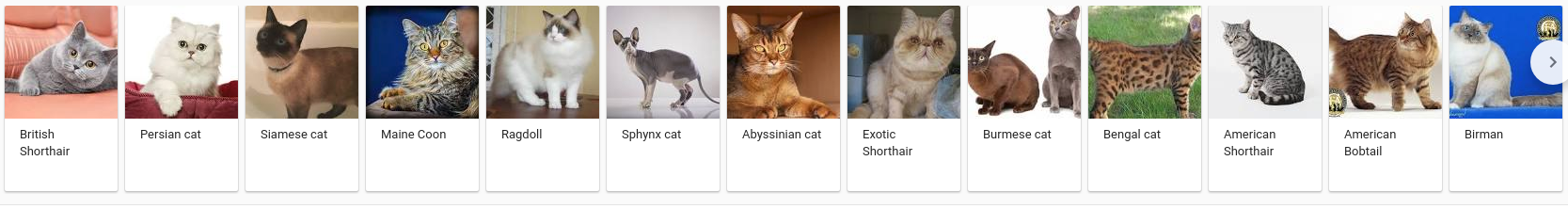

Well that’s a lot of variation to deal with - quite literally infinite. But wait - there’s more! We haven’t even gotten to describing the different cat breeds. There can’t be that many, right?

Well... maybe a few - also note that there are many variations between cats of the same breed.

What I described above with cats is known as nuisance variability - we don’t care about how the room is lit, what pose the cat is in, what angle the picture was taken from, or what breed the cat is. We just care if there is cat in the image or not. Nuisance variability is task dependent - since if we were trying to classify cat breeds, the cat breed would obviously matter. However, no matter what Computer Vision task you try to tackle, there will always be nuisance variability, more than in many other problems.

This comes from two things - the high dimensionality of the problem, and the complexity of the image formation process. When I say high dimensionality, I am referring to how an image has a lot of pixels. Even a small 96-by-96 image - an image size only used for small contact icons - has 9126 pixels. The color on each of these pixels can move in different directions. Images do have a great deal of structure to them (i.e. there are many pixels with the same color on a wall) so the actual number of independent variations (i.e. the number of ways the the pixels can change) in an image is much less than that, but still a huge amount to deal with..

The other part I mentioned, the complexity of the image formation process, is another big part. When you take a picture with your camera, light from your surroundings all bounces into the lens and hits the sensor inside your camera (assuming you have a digital camera - regular film works similarly though). As much as I would love to go into it, I’ll spare you the details of how this all works. Suffice it to say, it is a complicated process controlled by the lighting, movement, and geometry of what you are taking a picture of. Information of the original scene is lost in this, since you are going from the 3D world to a 2D image, losing a dimension of information. To interpret these images, we need to somehow encode this lost information of the world. How to do that is the topic of the next section.

Current State of the Art

The best technique to use for most tasks in Computer Vision is Deep Neural Networks (DNNs), alternatively deep learning. There are many articles describing these - and some courses (see here, here, here, here, here, here, and here). So going into too much detail would be redundant - I will stick to a high level summary. We want to take an image as input and get some output - say our cat example. Instead of manually specifying what operations to do with the pixels (gross...) we just gather a bunch of relevant examples, labeling them by hand. To be clear, I mean a huge amount - thousands and thousands of them.

We then use the examples to ‘train’ a DNN - essentially passing the image through a bunch of successive parameterized operations to get our estimate. To train this way, we also need some criterion for judging how wrong the DNN is, which is called a loss function. After passing the image through the operations, we get its estimate for what we want - cat or no cat. Unfortunately, as we have no idea what the proper parameters of the operations should be, we start out with an essentially useless answer. These successive operations are very complicated so we can’t just change the parameters of them to always get the right answer. However, using the loss function to see how wrong we are, we can see which way we can tweak the parameters to get a slightly better answer. This is why we need lots of examples - we keep tweaking the parameters of these operations little by little until we get closer to the right answer. The parameterized operations of the DNN have to be smooth, in a mathematical sense, or else this form of training won’t work (we’ll discuss this more in the next section).

When we parameterize these operations, we typically have many many redundant parameters to make the training process easier. However, this potentially lets the operations more or less memorize every image it has seen, rather than trying to to generalize to new images. To make sure this isn’t happening, we have an extra set of examples (of cats and not cats) that the network hasn’t been trained on (i.e. we haven’t tweaked its parameters on these examples). If it performs well on these, then we know that it has learned better general features and not just memorized things. If it does well on the examples we have shown it, but not well on examples outside of them, we call it overfitting.

Now for technical reasons researchers are still trying to fully understand, this works really well. As in, it blows all previous methods Computer Vision research tried out of the water (23% error to 4% error in one benchmark). Given that the DNN is over-parameterized and could just memorize the examples you give it; that in this tweaking process we haven’t made any guarantees that it gets to the best answer; that we have little way of interpreting the intermediate features - you might think that this process would end up spitting out nonsense. But variations of this method have produced the best results we have seen in image classification (the cat/not cat example), object detection (seeing where the cat is), pose estimation (seeing how the cat is posed), segmentation (labelling each of those horrible pixels as a cat or not a cat), and many more. It works so well, that Deep Neural Networks (more specifically a technical variant called Convolutional Neural Network which exploits the local structure of images) is often conflated with Computer Vision.

One area where the dominance of DNNs has not quite caught up is the area of 3D reconstruction (creating a 3D model from 2D images). There has been much research into this, but there hasn’t been any DNN-based method that can compete with the traditional methods. Traditional methods are essentially tracking small salient points across several images, then triangulating the points. There is a lot of error in this process, so optimization-based post processing, filtering out of bad points and large scale adjustment of 3D poses and point positions across all the images are crucial for good performance.

People suspect the difficulty of applying DNNs to this area arises because geometric constraints are quite complex and have been studied and refined for 30+ years by Computer VIsion researchers. It is also difficult if not impossible to find large scale the true 3D shape for the training examples we could give to a DNN. These combined make for a difficult problem with many researchers still trying to figure it out. I will give my own bias for a second and say that I think just throwing DNNs at this problem won’t work, and we’ll need to somehow incorporate the well studied geometric constraints into the models we build.

Limitations

Now that we have explored the state of Computer Vision, with DNNs and 3D reconstruction, we can explore what these things can do in more depth, and what their limitations are. There is a lot of hype in this area, and often people overstate the implications of their research. It is a marketing problem - more attention means more grant money, which incentivises over-promising. However, if you want to build a working system with a tool, you need to know how good that tool actually is.

For the most part, DNNs work really well wherever they work at all. So the cat/not cat problem and variations thereof are considering solved or close to solved. If you need to identify things in an image, then DNNs can work really well. There is also a lot of cool work on image generation (see NVIDIA’s work if you want an example). If you have a Computer Vision application in mind, DNNs should be your first go-to option.

Having given my endorsement of DNNs, I must give some caveats. Recalling the overfitting/memorization problem, DNNs won’t work very well unless you have a lot of data. This is why the big internet giants like Google and Facebook are so excited about deep learning - they have data in spades. There is some work on unsupervised training - training a DNN without labeled examples - but we haven’t figured that out yet. Which means if you want to use a DNN right now, you will need thousands or even millions of hand-labeled examples, which can be difficult. Also note that DNNs are not that smart - they tend to focus on surface level features, and won’t generalize well outside the domain they are trained in. To give a more concrete example, if you take a bunch of pictures of cats indoors to train your cat classifier, you would find it won’t do nearly as well for pictures of cats outdoors. So just remember, a DNN is only as good as its training data.

The other consideration is the structure of a DNN requires the operation to be ‘smooth’ in a mathematical sense. This limits our ability to train DNNs in certain scenarios. For instance, if an intermediate step of your algorithm requires a strict yes-no decisions (which has no smooth way of transitioning between different states) in the middle of inference, training a DNN can become difficult or impossible. This is why there is a great deal of research making hard decision problems ‘soft’ - assigning probabilities to decision outcomes as opposed to looking at only one decision path.

It is also difficult to add hard constraints on intermediate steps of a DNN’s computation. If you have a large amount of domain knowledge you would like to incorporate into the DNN you are training, we are fairly limited in how we can incorporate that. Unlike the previous problems, though, there are a few workarounds for this, such as pick appropriate loss functions for training to incorporate your knowledge, carefully picking the parameterized operations that the DNN uses, etc. However, it is difficult to give much advice without knowing the specifics of the problem, so you will need to get someone with go on this.

If 3D reconstruction is more up your alley, there are plenty of open source systems that work pretty well. That is not to say that they will work well right out of the box. A new application still needs to do significantly tuning for it to work. If you want an Augmented Reality application, then Android and iPhone already have kits ready for this. If you want a more robotics-oriented application then there are plenty of open source software packages (e.g. ROS, ORB SLAM) that do visual tracking and mapping. Typically you would need additional sensors on top of vision to do well in robotic applications, however.

Research Areas for the Future

There is active research in all of the problem areas described above. Getting good classifiers with less data is known as Few-Shot or One-Shot learning. Dealing with non-smooth operations is typically handled in Reinforcement Learning, but there are also creative ways around this constraint. Adding hard constraints into DNN training is actively investigated by many researchers looking to get 3D geometric constraints into DNNs. Some of the research to fix these problems is trying to combine DNNs with other methods to get the advantages of both. There are also more technical areas of research I will go over.

First: dealing with uncertainty in DNNs. In many useful practical applications, the output we want to model is inherently ambiguous. For instance, in weather prediction we lack enough sensor data to make deterministic predictions of the weather. In these cases what we need is for our DNN to output a distribution. However in our current training regime we have a loss function that just tells us how wrong we are for one example. It doesn’t tell us if the output is a reasonable prediction even if not 100% accurate. The current best way to handle this Generative Adversarial Models (GANs) - which generate images to match a distribution. There is also Bayesian Neural Networks, which model the DNN with respect to probabilities, naturally giving the output an uncertainty. The most famous example of this is Variational Autoencoders (VAEs). However, GANs are notoriously difficult to train, and VAEs tend to give very blurry outputs and lose important details. So there is still much research to be done on how to handle this uncertainty.

Another area of active research is security. People have found that you can add small perturbations to input images to give catastrophically wrong predictions - so with a few tweaks to the pixels your cat could be labeled an ostrich. They have found how to do this even if they don’t have access to parameters of the DNN model. They have even gotten real world objects to be misclassified. This has serious implications especially if we have robotic agents - this could allow the more malicious users out there to hack machine learning software. For instance, if they could force a misclassification of medical images or make a stop sign be classified as a green light, there could be some serious consequences. To make sure these large scale DNN frameworks are safe to use, we need to counter such attacks.

There is also the interpretation problem. Right now, to understand a DNN, you have to look at its output. The intermediate operations are difficult at best to understand. There are some crude tools to tell us what the DNN is doing on certain inputs but we lack sophisticated analysis tools. The problem is we lack a good mathematical description for the distribution of images (specifically their pixels), and analyzing the parameters trained on said images would require that. Analysis tools would be useful for both scientific and practical purposes. With sufficiently good analysis tools, we could debug and catch errors in our DNNs before they are deployed. On the scientific side, however, we still don’t understand what makes DNNs work so well on images. As DNNs are complicated objects (both practically and mathematically), we want to understand what makes them tick.

Finally there is the area of 3D reconstruction. There has been a bit of resurgence of research in this area in the Computer Vision community. Current 3D reconstruction systems work very well right now, but they are not so amenable to incorporating the power of DNNs, for reasons stated earlier. Thus people are trying to incorporate in DNNs into the 3D reconstruction pipeline. The hope would be to make these systems more robust to things like weather conditions and dynamic objects in the scene. This is my area of research so I see a lot of promise in marrying 3D reconstruction and DNNs, but I also think that just adding additional constraints to a DNN won’t be enough to solve this problem. Still, the surge of work for Augmented Reality and Self Driving cars means that there is a lot of work in this area.

Conclusion

This ends our brief tour of Computer Vision. We looked at the many difficulties facing Computer Vision for even a simple example like labelling a cat in an image. We then looked at modern solutions to those problems, especially DNNs. Throughouts this we’ve given many examples of what Computer Vision can do. With recent developments (especially DNNs) Computer Vision has come far in what it can do, and is at the point where practical applications are possible in fairly general environments, if only in specific applications. There is still a long way to go in terms of research, but we are making progress.