Deep Reinforcement Learning with Hierarchical

Recurrent Encoder-Decoder for Conversation

ABSTRACT

I co-led the project with Heejin Jeong, supervised by professor Lyle Ungar and Chris Callison-Burch. and built an intelligent dialogue system that was deployed on the Echo Dot. It is well known that dialogue systems relying on hand-crafted rules are too inflexible to handle the myriad of sentences in a natural conversation. And although current recurrent neural net based systems are more robust to input, they have a tendency to generate irrelevant or curt responses that terminates a conversation prematurely. We hypothesized that an engaging dialogue system should satisfy two criteria: it must incorporate the dialogue history when deciding what to say next, and it must be able to understand the future consequence of its utterances. We posed the “history aware” problem as an optimization problem with multiple objectives where by both likelihood of the current sentence given previous sentences, and the likelihood of the current word given previous words are maximized. This complex distribution is represented by a hierarchical neural net. We posed the “future aware” requirement as a deep reinforcement learning problem, whereby the dialogue agent optimized a conversation policy given specified future reward. Our model was trained on CALLHOME American English speech corpus as well as the OpenSubtitles corpus. The paper was submitted to a conference in DC and accepted for poster presentation.

INTRODUCTION

A long standing goal of artificial intelligence has been to program a computer that can carry on a conversation intelligently with a human being. The first milestone in this direction was ELIZA, created in 1964 at MIT Artificial Intelligence Laboratory by Dr. Joseph Weizenbaum. ELIZA simulated “the responses of a non-directional psychotherapist in an initial psychiatric interview,” a shrink asking open-ended questions. Some of its responses were so convincing that users became emotionally attached to the program. This led many academics at the time to believe that ELIZA could positively impact people’s mental well being. However, its rule based system was ultimately too restrictive for prolonged conversation, and this line of research was discontinued after the AI winter.

In recent years, the proliferation of home assistant devices such as the Alexa and Google Home led to a resurgence of interest in intelligent conversation agents, so called “chatbots.” Broadly speaking, chabots are expected to carry on two kinds of conversation: informational-retrieval based conversation where the user expects the correct answer for a specific query; and open-domain dialog, where the chatbot is expected to speak about any topic and be “interesting.” We focus on the second task, using the latest machine learning techniques to train an algorithm on conversation etiquette using transcripts from movie scripts and recorded phone calls.

TECHNICAL BACKGROUND

The next two sections describes the technical background required to understand this work. We assume a basic understanding of computer science, probability, and linear algebra. And reasonable familiarity with machine learning both in concept and practice.

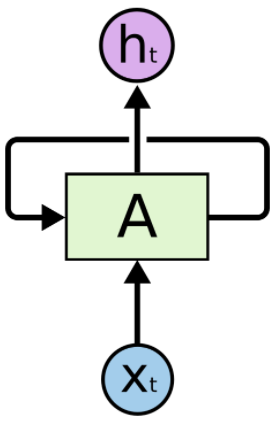

Recurrent Neural Network

We only provide a brief description of recurrent neural nets (RNNs) here. A great introduction to RNN and its popular extension the long short term memory networks (LSTM) can be found here. RNNs are a family of networks for processing sequences of values, i.e., sentences. For example in Fig 1, the RNN denoted by A will take in some word x in the English language, and output a “hidden” state h. Notably, the arrow that stems from A and loops back onto the box symbolizes the fact that the hidden output is a both a function of the input x, as well as the previous hidden state stored in the network. The representative power of RNNs stems from the fact it has short term memory spanning several symbols in the sequence, which is essential in natural language sentences that have long term dependencies. In practice, the memory capacity of RNNs proved insufficient to model real languages, thus the LSTMs architecture was introduced to explicitly model long term dependencies

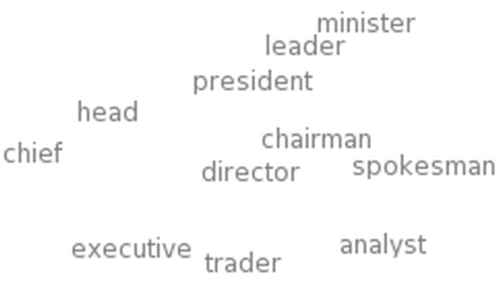

Finally, let us examine a specific RNN model and why it matters. In continuous bag-of-words model, the RNN is given news articles and must predict the current word given a window of surrounding context words. In this case, the input x is a one-hot representation while the output h is some n-dimensional vector. The power of model is evident when examining the hidden representations, semantically similar words are closer together under under cosine distance than those with dissimilar meanings. In a very rough sense, continuous bag-of-words relate meaning of words to geometry, also known as an embedding. There are numerous such models, collectively called word2vec. Although word2vec has performed admirably on certain word analogy tasks, there is no unique embedding that captures all the various relationships between words at the same time, ie antonyms, hypernyms, meronyms. In fact for many of these relationships, there is tremendous merit to explicitly learning them from data. Word2vec models certainly do not relate words to the myriad of entities they may symbolize. Therefore word2vec do not solve the symbol grounding problem

Reinforcement Learning

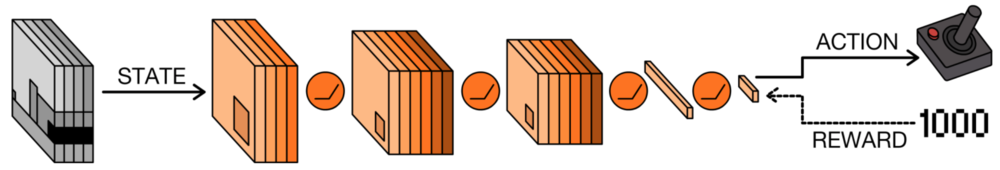

This section gives a gentle introduction to reinforcement learning (RL) and deep RL. The essence of RL is learning through interaction. An RL agent interacts with its environment and, upon observing the consequences of its actions, can learn to alter its own behaviour in response to rewards received. This paradigm of trial and error learning is rooted in psychology. Specifically, the autonomous agent has a set of actions A it can take on the environment, there is a set of states S, and a set of rewards R that the agent may receive upon each action. The agent will take an action a at each state s, and upon transitioning to a new state, receive a reward r from the environment. The agent’s goal is to determine a policy of which action to take in each state so that its reward is maximized at the end of the game. The simplest way to represent policy is as a table mapping states and actions to rewards. Historically, the states and actions of the game is constructed by hand, this is sufficient for simple games (such as tic-tac-toe) but do not scale well to games with high dimensional input and no clear heuristic as to how to represent the states. In the game Space Invaders (Fig 3) for example, the states could be every possible image frame over all possible space invaders games, and the action are all possible left, right, and shoot combinations the player could take. Therefore both the state space and the policy is too large so as to render the problem intractable. Deep RL promises to solve the intractability problem, for example a deep convolutional neural net is first used to compress the states in Space Invaders, then RL is used to approximate a policy with this reduced state space.

PROBLEM FORMULATION

This section describes how we formulated the problem of training an intelligent dialogue agent using LSTMs and Deep RL. We model the conversation as a sequence of utterances between two speakers, each utterance is composed of a sequence of words. The goal of the intelligent agent is then to output the “best” response given all previous utterances, and the expected reward of outputting this response.

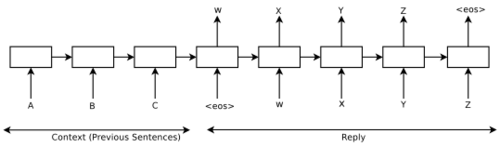

As a baseline, we replicated the work of Vinyals and Le (2015), who cast the best response given previous response as a sequence-to-sequence (seq2seq) learning problem. In seq2seq, an encoder LSTM reads the input sequence on token at a time, and keeps track of a hidden state that is updated upon each word read. This hidden state may be loosely interpreted as a “summary” of the sentence, sometimes referred to as an utterance vector. The summary vector is then passed to a decoder LSTM, which predicts the output sequence one word at a time, while updating the same utterance vector from the encoder LSTM. During training, the true output sequence is given to the decoder LSTM, and the model is trained to maximize the cross entropy of the correct sequence given its context.

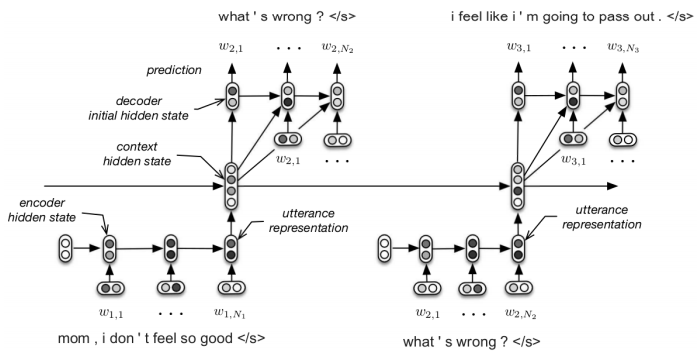

Next, we tested the hypothesis that the dialogue agent benefits from a richer representation of the conversation history. Specifically, we model the conversation as a random walk over a “discourse space”, where each vector in this space represent some abstract topic of the conversation. Then at each time point, the discourse vector is projected onto the utterance space, and a sequence of words is generated conditioned on this projected discourse vector. We represent this process using a hierarchical recurrent encoder-decoder architecture (HRED), first proposed by Sordoni et al. (2015a) for query prediction, and later adapted by Serban et al. (2016) for neural dialogue generation. Under this model, and encoder LSTM maps each utterance to an utterance vector. Then an higher-level context LSTM maps this utterance vector to the discourse vector, and propagates this discourse vector between conversations. The decoder LSTM is then used to generate the response conditioned on the discourse vector. Finally, both the baseline seq2seq model and HRED are trained by maximizing the log likelihood (MLE) of the entire session.

Baseline models trained using MLE objectives often output short-sighted and dull responses such as “I don’t know.” This is not surprising since the MLE objective does not capture the original intent of developing an open-domain dialogue agent that engages the user. We remedy this problem using deep reinforcement learning with hand-crafted reward functions. In our setting, the actions of the agent are the responses it can output, the states are defined by the previous two turns of the dialogue, while the policy is represented by the two baseline encoder-decoder networks we trained using the MLE objective. Following the work of Li et al. (2016), our reward function is a weighted sum of three hand crafted objectives that promote “engaging” dialogue behavior, and the weights are tuned heuristically during training time. The first objective penalizes “dull” responses, defined as eight or more consecutive responses of key phrase such as “I don’t know”, “I have no idea”, and “I don’t know what you’re talking about”, etc. The second function penalizes semantic similarly defined by the cosine distance of the utterance vector of the query and response, this prevents responses that simply paraphrase the user query. The last reward promotes semantic coherence, defined by the probability of the response given the previous state. When searching for the optimal policy using RL, we first initialized the policy using the encoder-decoder trained using the MLE objective, so that it already outputs plausible responses. Then we simulated a conversation between two dialogue agents so that they may find the optimal conversation policy.

DATA SET

The most important aspect of deep learning project is the volume of data and its relevance to the measures defined. Finding natural conversation data is particularly challenging due to privacy concerns, we had access to the following sets of data:

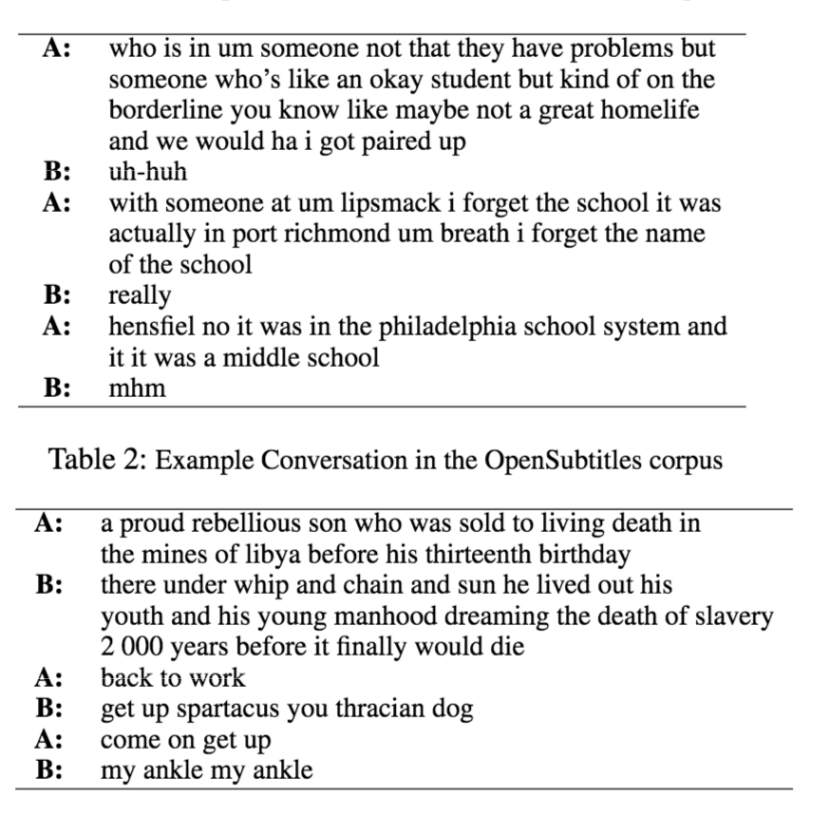

- The CALLHOME American English Speech Corpus (LDC97S42), with 120 thirty minute phone conversations between native English speakers.

- OpenSubtitles corpus with 28 movie scripts.

Note that relative to standard deep learning projects, our data set is very small. Furthermore, the distribution over utterances is not ideal given the goal of training an engaging conversation agent. In CALLHOME, one speaker often directed the conversation while the listener gave terse responses such as “mhm” or “okay”, in fact about 20% of the utterances in this dataset is “mhm”. This would bias naive maximum likelihood models to output short responses given long queries. The distribution of utterances in OpenSubtitles was significantly better with regards to uninformative responses, however it lacked topic coherence because the scripts were a concatenation of dialogues from different scenes, with no clear break token between the scenes.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

In this section we discuss the results of our experiment, and close with a broader critique on the limitations of deep learning applied to open domain conversations.

HRED

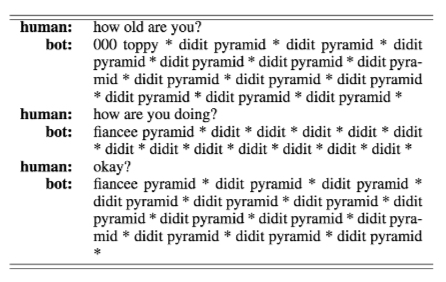

This model was trained for 5 days on a GeForce GTX TITAN X GPU. After five hours the model appears to have acquired a basic grammar, but have a tendancy to output repeated words. After training for 72 hours there is a marked decrease in sentences with repeated words, with some basic semblance of semantic relationship between question and query. In general, the results after five days do not appear qualitatively better than results after just 72 hours. In particular, we see no evidence that HRED is tracking “some” conversation state.

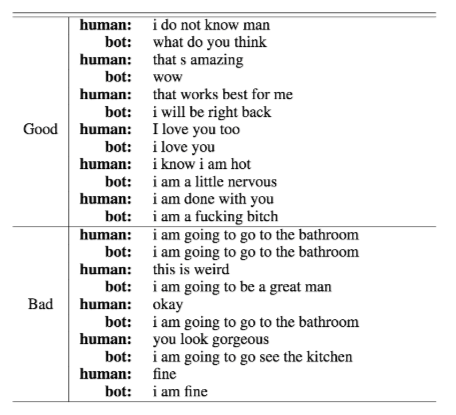

DRL-Seq2Seq

The training results of the backward SEQ2SEQ model after 109000 steps are presented in figure 9. Since it is a backward model, the bot generates the most likely utterance that will have the input utterance as its response. The examples in the Good section shows acceptable performance of the model, while those in the Bad section is unintelligible. The model tends to generate certain responses such as ”I am going to go to the bathroom”, or simply output repeated words. The training results of drl-seq2seq are in figure 10. These results are poor for two reasons. First, since the mutual information score is averaged by the number of words in a sentence and each term is negative (log probability), shorter responses score higher according to our objective. Secondly, it tends to generate repeated words in a sentence. Thus we added an additional reward for the number of words of an output sentence and penalized repeated words. However, the modified reward funtion did not improve the overall quality of the response.

CONCLUSION AND FUTURE WORK

Since GPU time is limited, we did not experiment deep reinforcement learning using HRED to structure the states. This is justified given the poor results from simpler models. Furthermore, there is sufficient results to diagnose the different reasons for poor performance, and modify our original hypothesis that deep reinforcement learning using a hierarchical recurrent neural network is the appropriate model to capture an engaging conversation.

Inspecting the results, we note two source of error: grammatical error and topic incoherence. Past work have show that Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) can capture English grammar statistics, and since HMMs are less complex than RNNs, we ascribe grammatical error in our case to insufficient data and poorly tuned model. We assert that RNNs are fundamentally capable of capturing grammar given sufficient effort. However, we are doubtful that sequence to sequence deep learning is the appropriate framework to build an engaging conversation agent amounting to more than parlor tricks. Deep learning have shown success in cases where the amount of data is vast and the information needed to complete a task is in the data set, however in the case of conversation we believe that the information needed to output a response is not necessarily in the data, irrespective of its size. This is because sentences are fundamentally cognitive constructs and the key to an appropriate response lies in facts about the world, and the intention of the speaker, neither of which appear to be in the corpus based on visual inspection. This fundamental fact may go unnoticed in the frenzy to chase better numbers. Just to highlight the futility of the task we direct your attention to figure 11 and consider some tasks in computer vision where deep learning has shown tremendous success:

- object recognition: is there a cup in the picture

- segmentation: delineate the boundaries of cup

- pose estimation: what is the orientation of the cup relative to an arbitrarily defined canonical pose

- 3D reconstruction: construct the cup in three dimensions given (possibly more than one) two dimensional images.

Not all of these questions are well posed, but they all address facts about the physical world where it is possible to either procure the ground truth or arbitrarily define one. However, if there is a computer vision task asking “what will you do with the cup,” then this question is fundamentally unanswerable by inspecting images of cups alone because the answer lies in the mind of the user, where it is not observed. The intention of “what to use a cup for” is a cognitive construct, and so too are words and sentences. Furthermore, imagine if we tried to answer the question by constructing a model trained on a massive corpus of Youtube videos of people using cups, and the current observation consists of the past five frames of this cup sitting on the table, and then predict how the next person will use this cup. It is clear to see that this endeavor is challenging regardless of how deep the stacked RNN is. And yet those who attempt to train an intelligent agent using corpus data alone are treading this exact path.

Note the argument here is far from original, Noam Chomsky made a similar critique as linguistics abadoned rational methods in favor of emperical models. Our critique is not based on ideology but rather practical considerations. We have to respect that one of the early success of statistical “AI” methods was in NLP, where accuracy in part of speech tagging leapt from mid 60% to low 90% with the introduction of HMMs. However, part of speech tagging differ significantly from open domain conversation in that the input is fully observed and the set of output strings is well defined (in this case labeled by people). A similar task with rich inputs and well defined outputs is voice to text, and deep learning has enjoyed tremendous success. Finally, machine translation among data-rich languages has also witnessed incremental advances due to deep learning. Once again the set of output utterances given any input is relatively constrained in settings that are of value, and simple measures such as N-gram overlap are fair objectives towards the goal. Thus the “art” of supervised learning applied to human constructs is to structure tasks so that the desired label can be observed. Based on our experiments, we believe sequence to sequence learning for conversation lacks imagination. And since the state space structured by stacked RNNs cannot capture informative features relative to the task, it would be difficult to use reinforcement learning to train an agent to navigate this space in a qualitatively satisfactory manner.

Anyone who has ever botched a phone interview or written an ill-worded email can attest to the fact most of effective communication is non-verbal, both body language and auditory cues are vital information in a proper dialogue. In fact past research by Zhou Yu and others demonstarted the efficacy of a conversation agent combining a computer vision pipeline that combines facial expression information with auditory and spoken cues. In practice, the primary challenge with this approach is privacy and the cost of deploying multimodal sensors capable of running inference onboard, however we believe this is the most profitable path forward.